I was always rooting for the underdog, though my winners never won. It was those last struggling seconds that seemed always to captivate me most, when it had to be then, or never. That razor’s edge, where one really knew about life and death, to make it or not to make it, to be victorious or vanquished. I pondered these thoughts often, or thoughts like these, though probably more vague and juvenile, while shivering in an empty enameled tub, glistening wet, at the glorious and tragic end of the game, of the ritual, staring at the shinny-rimmed hole, squatting and peering down, listening to those last gurgles that signified my “horse’s” loss once again.

We were young, before we learned how not to be naked. My sister and I took baths together in an old ball-foot tub. It was a smooth, glistening white tub, with faint hairline cracks in the enamel that looked like little spider webs. There was worn-out enamel around the drain that seemed sort of like a hole in the sole of a worn out shoe The water was always just a touch too hot, and entry was its own adventure. It was my time to prove my bravery to my little sister, and to my mother, who never seemed as impressed.

Mother would always take my sister out of the bath first, to work on her tangles. I stayed in longer because I was dirtier, because I was older, because I was a boy. After awhile my mother would say “pull the plug” and I would, with relish. For now, the game, the ritual, the race began again.

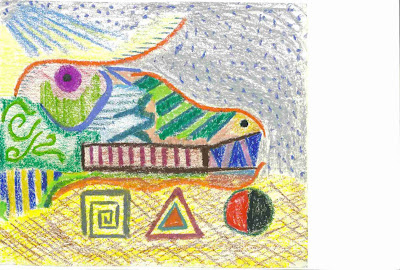

Carefully, I placed some piece of flotsam behind me, at the far end of the tub from the faucets, from the drain, and observed, noting its characteristics. These were my horses, my winners: a hair, a floating chunk of soap, perhaps some lint. Then I pulled the plug, fired the starting gun, flung open the gates.

First there was the sound, the rush of water filling the empty pipes and then a subtle disturbance on the surface followed by the slow movement of water. I tracked the flotsam horse with g rowing anticipation, monitoring the water’s growing momentum, watching the awkward dance of the little whirlwind over the drain.

As the water level lowered, I shifted to a kneeling position, watching my long-shot go around me or through my legs, at which point I would squat, positioned to watch my horse win, my horse overcome the odds, overcome the current, the gravity, and demonstrate to me, to the world, at long last, victory. Victory over inevitability, over all that which is predetermined or fore-ordained, of all that is ruled by rules and probability. Often at this point I would vaguely become aware of my mother’s voice somewhere in the distance asking me to hurry. But I squeezed it out. The race was on, the ritual begun.

I knew almost “by-heart” the path my horse would take. Straight down the middle until, picking up steam, he would swing to the left, suddenly caught in the pull, but fighting outward. He would struggle, and I would agonize for him, trying to will him free, to desire for him victory so intensely that he broke the spell. The more the concentric rings tightened, the more the orbit closed around the drain, the more focused I became, and the more anxious. Though the whole race was actually over in seconds, the space in my mind’s time reckoning was vacuous and seemingly eternal, a lifetime of almost suspended, breath holding, vicarious clinging to the precipice. And then it would end, my horse having disappeared, down the drain.

There was always a delayed reaction within me; I would stare for a moment in disbelief, incredulously, and then suddenly and expectantly, but with a familiar dread, spring towards the drain to peer down the dark hole, hoping against hope. But there was nothing,

just the familiar gurgling sound, and the slow dawning of disappointment and frustration,

as I simultaneously became aware of my foolish position, cold, wet, naked, squatting in the empty tub, and mother calling.

Originally appears in Voice of the Hill, Vol. 3, No. 4 July 2001